EXHIBITION

AN ALCHEMY OF MATTER

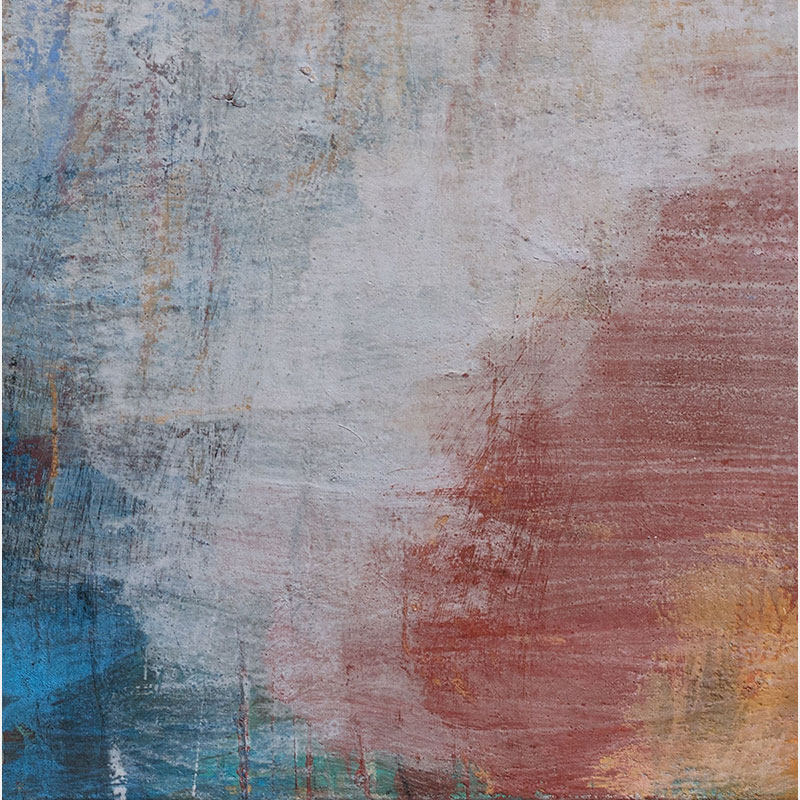

Orazio De Gennaro:

Tempo Perso, 2011

Oil Pastel, Graphite, and Pigment on Canvas

44 x 48 in

112 x 122 cm

US $ 7,300

In Tempo Perso, Orazio De Gennaro creates a field where color and matter dissolve into one another, evoking both the slow erosion of walls and the vastness of skies. Broad swathes of black, blue, ochre, and white appear suspended between opacity and light, rendering time not as a straight line but as layered presence. The work resists depiction, instead offering an atmospheric space of memory and transformation. ...more

Go to Artwork: NEXT PREV ALL